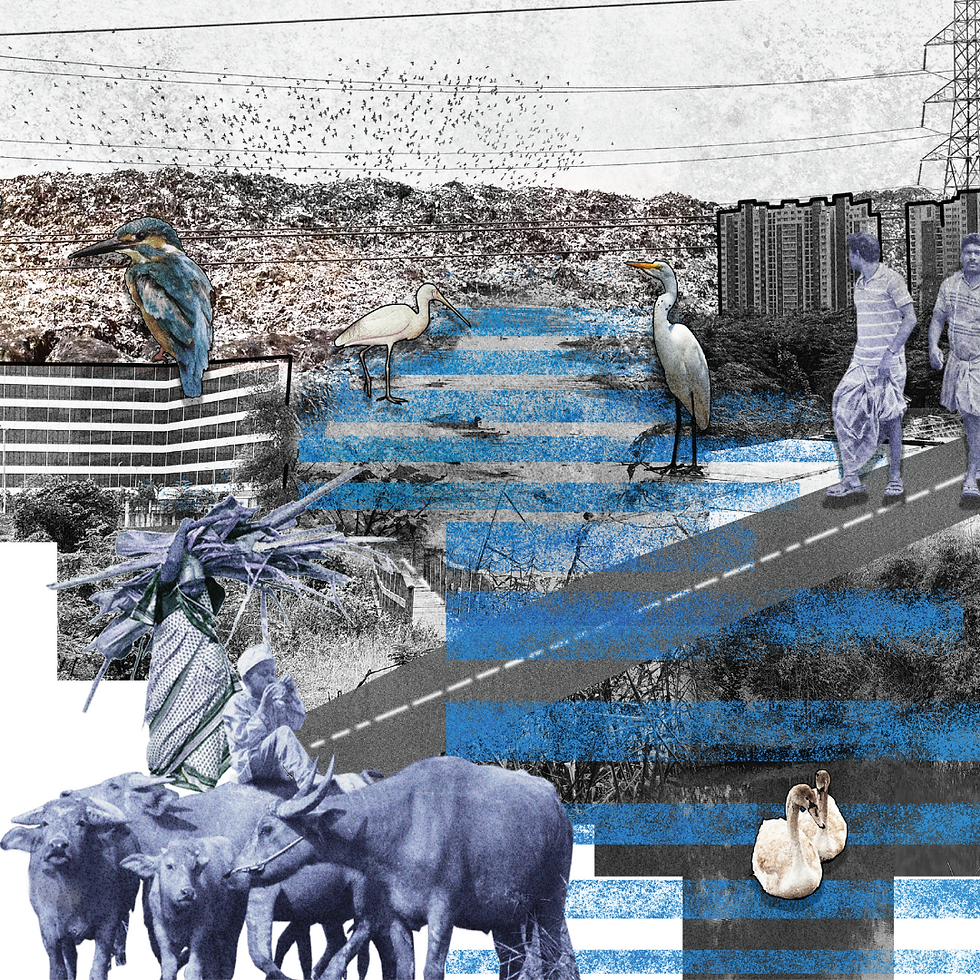

Mapping the challenges in Pallikaranai Marshland

Chennai’s last major wetland shows how labelling marshes as wastelands enables ecological loss and urban vulnerability.

Thisai and Prakriti

March 2024

A longer article is coming soon. For now, we urge you to read the core of our research and join the conversation it invites.

In a riveting spectacle of nature’s fury, a huge surge of water shattered the compound wall of an apartment complex in Pallikaranai, a district in south Chennai.

With an unbridled force, the water seized control, washing away numerous automobiles and motorcycles and mercilessly tossed them about. As the residents of Chennai watched this disastrous event with utter dismay play out as a “viral” video on their smartphones, a profound query echoes through the collective conciousness: are we in reality exercising smartness and wisdom in our pursuit of progress and development?

Despite the availability of resources for future steps, eight years later, in 2023, citizens of Chennai seem to be back in square one.

Let’s take a step back to explore this.

The importance and vitality of the Pallikaranai marshland for the city of Chennai has been well established by many experts from different fields through their respective standpoints - ecological, environmental and hydrological. Home to around 381 species of flora and fauna, the marshland has been recognised as a biodiversity hotspot and natural habitat of certain endangered species. It is important to note that though the Pallikaranai marshland is known as a single entity, it is actually a system of multiple wetlands, part of the South Chennai Wetland complex.

This complex consists of over 30 wetlands which drain into the Pallikaranai marshland. Further, the water held by it drains into the Bay of Bengal through the Okkiyanmadavu canal and the Kovalam creek. On the whole, the marsh acts as a watershed for roughly an area of 250 sqm. The marsh is a low lying area that runs parallel to the Buckingham canal constituting pockets of aquatic grass species, water, scrub and marsh. Throughout history, the Pallikaranai marshland and the area around it have acted as a sponge for excess storm water runoff and as a natural water holding zone for the entire city. However, the Velachery-Tambaram main road, 200ft radial road and the Rajiv Gandhi salai that cut through the marshland have cut off drain connectivity at many places.

Today, the extent of the Pallikaranai marshland is only 600 Ha - an alarming 90% reduction from its span of 6000 Ha in the 1990s due to multi-various industrial, educational and civic development activities.The January 2024 survey submitted to the National Green Tribunal (NGT) by the GoTN, states that out of 1,206.59ha of the Ramsar certified marshland, 38% has been legally and illegally occupied by the GCC (173.56 ha), ELCOT(163.25 ha), Railways (46.92 ha) and an IT Park (5.85 ha). The forest department controls only 749 ha. Large portions of the marshland falling under the districts of Thoraipakkam, Pallikaranai and Perungudi have been reclaimed and converted into residential colonies. Roads, infrastructure, municipal solid waste landfill, sewage treatment plant have further fragmented the marsh greatly disturbing the natural drainage patterns. Till when are we going to validate mindless construction in the name of development?

The CAG Report released in 2017 on Flood Management and response in Chennai and its suburban areas in the aftermath of the 2015 floods, clearly state that the GoTN’s decision to allow construction, on a stretch of 500m, on either side of the Rajiv Gandhi Salai to facilitate development of the IT industry is a major reason for this decline. CareEarth trust states that this problem is much more deep rooted and attributes its origin to the wrong land classification of the marsh as a ‘wasteland” by the revenue department up until the early 2000s. Owing to this classification, the marsh was seen as a rare greenfield site located in the immediate outskirts of the city. This misjudgement paved the way for various development projects, narrowly avoiding a golf course and a waste to energy plant. Over the course of many years, a massive 300ft high dumpyard has been formed in the marshland. Several studies show that extremely high level of toxins are present in the marsh’s water and soil. This has undoubtedly had some severe health impacts - ranging from skin disorders to lung ailments to contamination of breast milk - on local residents

In 1998, the National Environmental Engineering Research Institute (NEERI) of India recommended protecting government lands in Pallikaranai between the MMRD scheme road and the Shollinganallur-Perumbakkam road from urban development. However, the subsequent establishment of the ELCOT SEZ contradicted this advice. It is shocking to learn that as recent as 2010 the Madras High Court ruled that the “marshy land” was not worthy of protection as a wetland.

Ironically, parallel to construction activities that persistently encroach upon the ecologically sensitive wetlands, the marshland was also part of several conservation strategies. Firstly, it was identified as one among 94 wetlands of the National Wetland Conservation and Management Programme (NWCMP) by Govt. Of India in 1985-86. Following the 2015 Chennai floods, the GoTN has been meticulously drafting proposals of no less than Rs. 100 Crores, dedicated towards the preservation of the marshland and its surrounds.

In 2018, the Tamil Nadu State Wetland Authority was established in accordance with the Wetlands (Conservation and Management) Rules, 2017 mandated by the Union Environment Ministry. In April 2022, environmentalists placed substantial hope for the preservation of marshland after it attained recognition as a Ramsar site of international significance.However, the aftermath of the Michaung Cyclone raises profound concerns about the efficacy of the conservation efforts in marshland. Despite some successful funding, tangible efforts on site seem to be absent. Only specific portions delineated as a reserve forest in 2007 by the Forest Department of Tamil Nadu, are safeguarded against encroachment. This classification was was secrued through relentless lobbying by the Save Pallikaranai Marshland Forum, spearheaded by passionate local residential associations and through interventions of Tamil Nadu Pollution Board.

That we are losing the marshland to the plethora of urban-centric anthropogenic activities, in spite of the above-mentioned conservation strategies, would be an understatement. These activities have permanently altered the fundamental geographic characteristics of the land. Reclamation efforts would yield only buffer zones, lacking their original sponge-like properties. The GoTN’s proposal in 2023 for regular dredging of the Pallikaranai marshland, once dismissed in 2020 due to heightened waterlogging risks, underscore the need for scientifically informed solutions balancing conservation and development goals.

What is necessitated is an adaptive management strategy - one characterised by flexibility, inclusivity and knowledge-based decision making. Reimagining the marshland as interconnected wetlands systems, rather than an isolated entity, is crucial for effective management and addressing Chennai’s waster stagnation. The Comprehensive Management Plan for Pallikaranai marshland (CMPPM), drafted by the CareEarth Trust echoes these sentiments. Annexing the remaining portions of the marshland to the existing Pallikaranai Marshland reserve forest would aid in maximisation of its hydrological efficiency. Prioritizing the biomining of the garbage dump present is crucial due to several compelling studies highlighting alarming levels of mercury, cadmium and lead contamination in the marsh’s water and soil. It is imperative that the CMDA approach the marsh with a resolute commitment to its conservation, halting any future construction immediately. As there are multiple authorities that extend some form of control over the marsh, it is crucial for the various departments to work in harmony in order to create a positive impact and swift change.

Amidst this bleak scenario, a ray of hope may yet emerge. The Union Budget 2023-24, under one of its seven priorities, Green Growth, has initiated the “Amrit Dharodar” scheme that aims to promote optimal use of wetlands around the country. Last year, the GoTN has initiated the ‘Tamil Nadu Wetlands Mission’ for a period of five years from 2021-22 to 2025-26, with a budget of Rs. 115.15 Crores. This mission falls under the stewardship of the Tamil Nadu Green Climate Company, a special purpose vehicle (SPV) set up by the state government to achieve climate resilience in the state. However, despite its theoretical brilliance, conscientious citizens can’t help but recall another SPV - the Smart Cities Mission - and its unfortunate impact on stormwater drains of Chennai. Following the land survey conducted on the Pallikaranai marshland in 2024 and its subsequent submission to the NGT, the directive has been issued for the GoTN to vacate the occupied 38% of the marshland. Challenging as it may be, optimistic citizens hope for a distinctive outcome this time, deviating from 1998 scenario described above. There is an urgent need for political will, local legeslative bodies and judiciary to work in unison to preserve what is left of this ecologically sensitive marshland.

Sudden, short episodes of intense rainfall are poised to become more frequent and increasingly severe as a result of climate change. If we persist in maintaining a nonchalant attitude towards the conservation of Chennai’s wetlands - only awakening in the aftermath of disastrous episodes, engaging in discussions for a few weeks post-incident and subsequently relegating the issue to oblivion - then the city is bound to face even more severe water stagnation events starting as early as November or December 2024. It is high time we realise that the pursuit of construction in the marshland in the guise of “development” has proven futile, as nature inevitably asserts its supremacy in the end.